What Role Does the Family Play on Political Socialization

six.ii Political Socialization

Learning Objectives

Later on reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How practice people develop an understanding of their political civilization?

- What is political socialization, and why is it important?

- What constitutes a political generation?

This section will define what is meant by political socialization and detail how the process of political socialization occurs in the United states of america. It volition outline the stages of political learning across an individual's life course. The agents that are responsible for political socialization, such as the family and the media, and the types of information and orientations they convey will be discussed. Group differences in political socialization will be examined. Finally, the department will accost the ways that political generations develop through the political socialization process.

What Is Political Socialization?

People are inducted into the political culture of their nation through the political socialization procedure (Greenstein, 1969). Most frequently older members of society teach younger members the rules and norms of political life. However, young people tin can and do actively promote their own political learning, and they can influence adults' political behavior as well (McDevitt & Chaffee, 2002).

Political scientists Gabriel Almond and James Coleman once observed that we "do not inherit our political behavior, attitudes, values, and knowledge through our genes" (Almond & Coleman, 1960). Instead, nosotros come up to understand our role and to "fit in" to our political civilization through the political learning process (Conover, 1991). Political learning is a broad concept that encompasses both the agile and passive and the formal and breezy means in which people mature politically (Hahn, 1998). Individuals develop a political cocky, a sense of personal identification with the political world. Developing a political cocky begins when children offset to feel that they are role of a political community. They acquire the knowledge, behavior, and values that assistance them embrace regime and politics (Dawson & Prewitt, 1969). The sense of existence an American, which includes feeling that one belongs to a unique nation in which people share a conventionalities in autonomous ideals, is conveyed through the political learning process.

Political socialization is a particular blazon of political learning whereby people develop the attitudes, values, beliefs, opinions, and behaviors that are conducive to becoming practiced citizens in their land. Socialization is largely a ane-mode process through which young people proceeds an understanding of the political world through their interaction with adults and the media. The process is represented by the following model (Greenstein, 1969):

who (subjects) → learns what (political values, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors) → from whom (agents) → under what circumstances → with what furnishings.

Agents of socialization, which include parents, teachers, and the mass media, convey orientations to subjects, who are mostly passive. For example, parents who have an active part in politics and vote in every election often influence their children to do the aforementioned. Immature people who see television coverage of their peers volunteering in the community may take cues from these depictions and engage in community service themselves. The circumstances under which political socialization can accept place are virtually limitless. Young people can be socialized to politics through dinner conversations with family members, watching television and movies, participating in a Facebook group, or texting with friends. The furnishings of these experiences are highly variable, every bit people can accept, reject, or ignore political letters.

People develop attitudes toward the political system through the socialization process. Political legitimacy is a belief in the integrity of the political system and processes, such as elections. People who believe strongly in the legitimacy of the political system have confidence that political institutions volition be responsive to the wants and needs of citizens and that abuses of governmental ability will exist held in bank check. If political leaders appoint in questionable behavior, there are mechanisms to hold them accountable. The presidential impeachment process and congressional ethics hearings are two such mechanisms.

Political efficacy refers to individuals' perceptions almost whether or not they can influence the political process. People who take a potent sense of political efficacy feel that they have the skills and resources to participate finer in politics and that the regime will be responsive to their efforts. Those who believe in the legitimacy of the political system and are highly efficacious are more than likely to participate in politics and to have potent stands on public-policy issues (Craig, 1993). Citizens who were frustrated almost the poor country of the economy and who felt they could influence the political process identified with the Tea Party in the 2010 election and worked to elect candidates who promised to deal with their concerns.

Much political socialization in the Usa passes on norms, customs, behavior, and values supportive of republic from one generation to the adjacent. Americans are taught to respect the autonomous and capitalist values imbedded in the American creed. Young people are socialized to respect authorities, such as parents, teachers, constabulary officers, and fire fighters, and to obey laws.

The goal of this type of socialization is deliberately intended to ensure that the democratic political system survives even in times of political stress, such equally economic crisis or war (Dennis, Easton, & Easton, 1969). One indicator of a stable political system is that elections take place regularly following established procedures and that people recognize the outcomes equally legitimate (Dennis, Easton, & Easton, 1969). Most Americans quickly accepted George W. Bush as president when the 2000 election deadlock ended with the Supreme Court decision that stopped the recounting of disputed votes in Florida. The country did non experience tearing protests after the decision was announced, only instead moved on with politics as usual (Conover, 1991).

Video Prune

2000 Presidential Election Bush vs. Gore

(click to meet video)

This denizen-produced video shows peaceful protestors outside of the Supreme Court as the case of Bush 5. Gore was being considered to make up one's mind the outcome of the 2000 presidential election.

Some scholars contend that political socialization is akin to indoctrination, as it forces people to conform to the status quo and inhibits freedom and creativity (Lindbolm, 1993). Yet, socialization is non always aimed at supporting democratic political orientations or institutions. Some groups socialize their members to values and attitudes that are wildly at odds with the status quo. The Latin Kings, one of the largest and oldest street gangs in the United States, has its ain constitution and formal governing structure. Leaders socialize members to follow gang rules that emphasize an "all for one" mentality; this includes strict internal subject field that calls for physical assault confronting or expiry to members who violate the rules. Information technology also calls for vehement retribution against rival gang members for actions such every bit trafficking drugs in the Kings'southward territory. The Kings have their own sign language, symbols (a five-point crown and tear drop), colors (blackness and aureate), and holidays (January 6, "King'south Holy Day") that bond members to the gang (Padilla, 1992).

Political Socialization over the Life Class

Political learning begins early in childhood and continues over a person'southward lifetime. The evolution of a political self begins when children realize that they belong to a detail town and eventually that they are Americans. Awareness of politics as a distinct realm of experience begins to develop in the preschool years (Dennis, Easton, & Easton, 1969).

Younger children tend to personalize government. The offset political objects recognized by children are the president of the United States and the police officer. Children tend to idealize political figures, although immature people today take a less positive view of political actors than in the by. This trend is partially a effect of the media's preoccupations with personal scandals surrounding politicians.

Young people frequently have warm feelings toward the political system. Children can develop patriotic values through school rituals, such as singing the "Star Spangled Banner" at the start of each twenty-four hours. As children mature, they become increasingly sophisticated in their perceptions almost their place in the political globe and their potential for interest: they learn to chronicle abstract concepts that they read about in textbooks like this one to existent-world actions, and they start to associate the requirements of republic and majority rule with the need to vote when they reach the historic period of twenty-1.

Figure 6.seven

Young people who participate in community service projects tin develop a long-term commitment to volunteering and political participation.

People are the nigh politically impressionable during the catamenia from their midteens through their midtwenties, when their views are non set and they are open to new experiences. Higher allows students to run across people with various views and provides opportunities for political engagement (Niemi & Hepburn, 1995). Young people may join a cause because it hits close to dwelling house. After the media publicized the case of a student who committed suicide later on his roommate allegedly posted highly personal videos of him on the Cyberspace, students around the country became involved in antibullying initiatives (Sapiro, 1983).

Significant events in adults' lives can radically alter their political perspectives, particularly as they have on new roles, such as worker, spouse, parent, homeowner, and retiree (Steckenrider & Cutler, 1988). This type of transition is illustrated past 1960s educatee protestors confronting the Vietnam State of war. Protestors held views different from their peers; they were less trusting of authorities officials but more efficacious in that they believed they could change the political system. However, the political views of some of the most strident activists inverse after they entered the task market and started families. Some became government officials, lawyers, and business executives—the very types of people they had opposed when they were younger (Lyons, 1994).

Figure 6.8

Pupil activists in the 1960s protested against US involvement in the Vietnam War. Some activists developed more than favorable attitudes toward government as they matured, had families, and became homeowners.

Even people who have been politically inactive their entire lives can get motivated to participate as senior citizens. They may detect themselves in demand of health intendance and other benefits, and they accept more fourth dimension for involvement. Organizations such as the Gray Panthers provide a pathway for senior citizens to get involved in politics (Miles, 1997).

Agents of Political Socialization

People develop their political values, beliefs, and orientations through interactions with agents of socialization. Agents include parents, teachers, friends, coworkers, armed forces colleagues, church associates, order members, sports-squad competitors, and media (Dawson & Prewitt, 1969). The political socialization process in the United States is mostly haphazard, informal, and random. There is no standard ready of practices for parents or teachers to follow when passing on the rites of politics to future generations. Instead, vague ideals—such as the textbook concept of the "model citizen," who keeps politically informed, votes, and obeys the law—serve as unofficial guides for socializing agencies (Langton, 1969; Riccards, 1973).

Agents can convey knowledge and understanding of the political globe and explain how it works. They can influence people'southward attitudes almost political actors and institutions. They likewise can testify people how to go involved in politics and community work. No unmarried agent is responsible for an individual's entire political learning experience. That experience is the culmination of interactions with a variety of agents. Parents and teachers may work together to encourage students to take role in service learning projects. Agents also may come into conflict and provide vastly different messages.

We focus here on four agents that are important to the socialization process—the family unit, the school, the peer group, and the media. At that place are reasons why each of these agents is considered influential for political socialization; there are also factors that limit their effectiveness.

Family

Over forty years ago, pioneering political-socialization researcher Herbert Hyman proclaimed that "foremost amid agencies of socialization into politics is the family" (Hyman, 1959). Hyman had skilful reason for making this assumption. The family has the primary responsibility for nurturing individuals and meeting bones needs, such as nutrient and shelter, during their formative years. A hierarchical ability structure exists within many families that stresses parental authority and obedience to the rules that parents establish. The strong emotional relationships that be between family unit members may compel children to adopt behaviors and attitudes that will delight their parents or, conversely, to rebel confronting them.

Parents tin can teach their children about government institutions, political leaders, and electric current issues, just this rarely happens. They tin can influence the evolution of political values and ideas, such equally respect for political symbols or conventionalities in a particular cause. The family equally an agent of political socialization is almost successful in passing on basic political identities, specially an affiliation with the Republican or Democratic Parties and liberal or conservative ideological leanings (Dennis & Owen, 1997).

Children can learn by example when parents act as office models. Young people who observe their parents reading the newspaper and following political news on television may adopt the habit of keeping informed. Adolescents who back-trail parents when they attend public meetings, broadcast petitions, or engage in other political activities stand up a better risk of becoming politically engaged adults (Merelman, 1986). Children can sometimes socialize their parents to become agile in politics; participants in the Kids Voting Usa program have encouraged their parents to discuss campaign issues and have them to the polls on Election Day.

The home environment tin either support or discourage young people's involvement in political affairs. Children whose parents talk over politics frequently and encourage the expression of strong opinions, fifty-fifty if information technology ways challenging others, are likely to become politically agile adults. Immature people raised in this type of family volition oftentimes initiate political discussion and encourage parents to go involved. Alternatively, immature people from homes where political conversations are rare, and airing controversial viewpoints is discouraged, tend to abstain from politics every bit adults (Saphir & Chaffee, 2002). Politics was a central focus of family unit life for the Kennedys, a family that has produced generations of activists, including President John F. Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy.

Figure 6.9

Members of the Kennedy family unit have been prominently involved in politics for over a century, illustrating how the desire to participate in politics is passed on generationally.

In that location are limitations on the effectiveness of the family as an agent of political learning and socialization. Nearly families are not like the Kennedys. For many families, politics is non a priority, every bit they are more concerned with issues related to 24-hour interval-to-day life. Few parents serve equally political role models for their children. Many activities, such as voting or attending town meetings, take place outside of the home (Merelman).

School

Some scholars consider the school, rather than the family, to exist the well-nigh influential amanuensis of political socialization (Hess & Torney, 1967). Schools can stimulate political learning through formal classroom education via civics and history classes, the enactment of ceremonies and rituals such as the flag salute, and extracurricular activities such as student government. Respect for government is emphasized, every bit teachers take the ability to reward and punish students through grades.

The nearly important job of schools as agents of political socialization is the passing on of cognition about the fundamentals of American government, such as constitutional principles and their implications for citizens' date in politics. Students who master these fundamentals feel competent to participate politically. They are likely to develop the habit of following politics in the media and to become active in community affairs (Nie, Junn, & Stehlik-Barry, 1996).

The college classroom can be an surround for socializing young people to politics. Faculty and student exchanges tin form, reinforce, or change evaluations of politics and government. A famous study of women students who attended Bennington College during the Smashing Depression of the 1930s illustrates how the higher feel can create long-lasting political attitudes. The Bennington women came predominantly from wealthy families with bourgeois values. The faculty consisted of political progressives who supported the New Bargain and other social programs. Nearly ane-tertiary of the Bennington women adopted the progressive ideals of their teachers. Many of these women remained active in politics their entire lives. A number became leaders of the women'southward rights movement (Alwin, Cohen, & Newcomb, 1991).

Effigy 6.10

Women at Bennington Higher in the 1930s became agile in community affairs every bit a result of their political socialization in college.

While schools have slap-up potential as agents of political socialization, they are not always successful in pedagogy fifty-fifty basic facts about authorities to students. Schools devote far less fourth dimension to civics and history than to other subjects that are considered to be basic skills, such every bit reading and math. The average amount of classroom fourth dimension spent on civics-related topics is less than forty-five minutes per calendar week nationwide, although this effigy varies widely based on the schoolhouse. Students whose exposure to civics is exclusively through lectures and readings generally memorize facts nearly government for tests but do not call back them or make connections to real-world politics. The about effective civic teaching programs engage students in activities that prepare them for the existent earth of politics, such as mock elections and legislative hearings (Niemi & Junn, 1998).

Peer Group

Peers (a group of people who are linked past common interests, equal social position, and similar age) can exist influential in the political socialization process. Young people want approving and are likely to adopt the attitudes, viewpoints, and behavior patterns of groups to which they vest. Different the family and school, which are structured hierarchically with adults exercising authorisation, the peer group provides a forum for youth to interact with people who are at similar levels of maturity. Peers provide role models for people who are trying to fit in or become pop in a social setting (Walker, Hennig, & Krettenauer, 2000).

Peer-grouping influence begins when children reach school age and spend less time at abode. Middle-babyhood (elementary school) friendships are largely segregated by sexual practice and historic period, as groups of boys and girls will engage in social activities such as eating together in the lunchroom or going to the mall. Such interactions reinforce sex-role distinctions, including those with political relevance, such as the perception that males are more than suited to concord positions of say-so. Peer relationships change later in babyhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, when groups are more oft based on athletic, social, academic, and task-related interests and abilities (Harris, 1995).

The pressure to conform to group norms tin can have a powerful impact on young people's political development if group members are engaged in activities directly related to politics, such as pupil government or working on a candidate's campaign. Young people even will change their political viewpoints to conform to those held by the virtually vocal members of their peer group rather than face being ostracized. Still, individuals often gravitate toward groups that hold beliefs and values similar to their own in gild to minimize conflict and reinforce their personal views (Dey, 1997). As in the example of families, the influence of peer groups is mitigated by the fact that politics is not a high priority for nearly of them.

Media

Equally early every bit the 1930s, political scientist Charles Merriam observed that radio and motion picture had tremendous power to educate: "Millions of persons are reached daily through these agencies, and are greatly influenced by the material and interpretations presented in impressive form, incessantly, and in moments when they are open up to proposition" (Merriam, 1931). The chapters of mass media to socialize people to politics has grown massively equally the number of media outlets has increased and as new technologies allow for more interactive media experiences. Most people'south political experiences occur vicariously through the media because they do non have personal access to government or politicians.

Since the advent of television, mass media accept get prominent socialization agents. Young people's exposure to mass media has increased markedly since the 1960s. Studies indicate that the typical American aged ii to eighteen spends almost 40 hours a week consuming mass media, which is roughly the equivalent of holding a total-time task. In one-tertiary of homes, the television is on all twenty-four hour period. Young people's mass-media experiences oft occur in isolation. They spend much of their fourth dimension watching television, using a computer or jail cell phone, playing video games, or listening to music alone. Personal contact with family members, teachers, and friends has declined. More than than 60 percentage of people under the age of twenty have televisions in their bedrooms, which are multimedia sanctuaries (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006).

The employ of more than personalized forms of media, such as text messaging and participation in social networking sites, has expanded exponentially in recent years. Young people using these forms of media have greater control over their ain political socialization: they tin choose to follow politics through a Facebook group that consists largely of close friends and assembly with similar viewpoints, or they may decide to avoid political fabric altogether. Young people, even those who have not reached voting age, tin can get involved in election campaigns by using social media to contribute their own commentary and videos online.

Media are rich sources of data about government, politics, and electric current diplomacy. People learn about politics through news presented on television, in newspapers and magazines, on radio programs, on Internet websites, and through social media. The press provides insights into the workings of government by showcasing political leaders in activity, such as gavel-to-gavel coverage of Congress on C-SPAN. People can witness politicians in action, including on the campaign trail, through videos posted on YouTube and on online news sites such every bit CNN and MSNBC. Entertainment media, including television comedies and dramas, music, film, and video games also contain much political content. Television programs such equally The West Wing and Police and Order offering viewers accounts of how government functions that, although fictionalized, tin appear realistic. Media also establish linkages between leaders, institutions, and citizens. In dissimilarity to typing and mailing a alphabetic character, it is easier than ever for people to contact leaders straight using email and Facebook.

Some factors work against the media as agents of political socialization. Media are first and foremost profit-driven entities that are not mandated to be borough educators; they balance their public service imperative confronting the desire to make money. Moreover, dissimilar teachers, journalists do not accept formal training in how to educate citizens almost government and politics; equally a result, the news often can be more sensational than informative.

Grouping Differences

Political learning and socialization experiences can differ vastly for people depending on the groups with which they associate, such equally those based on gender and racial and indigenous background. Certain groups are socialized to a more agile role in politics, while others are marginalized. Wealthier people may have more resources for participating in politics, such as money and connections, than poorer people.

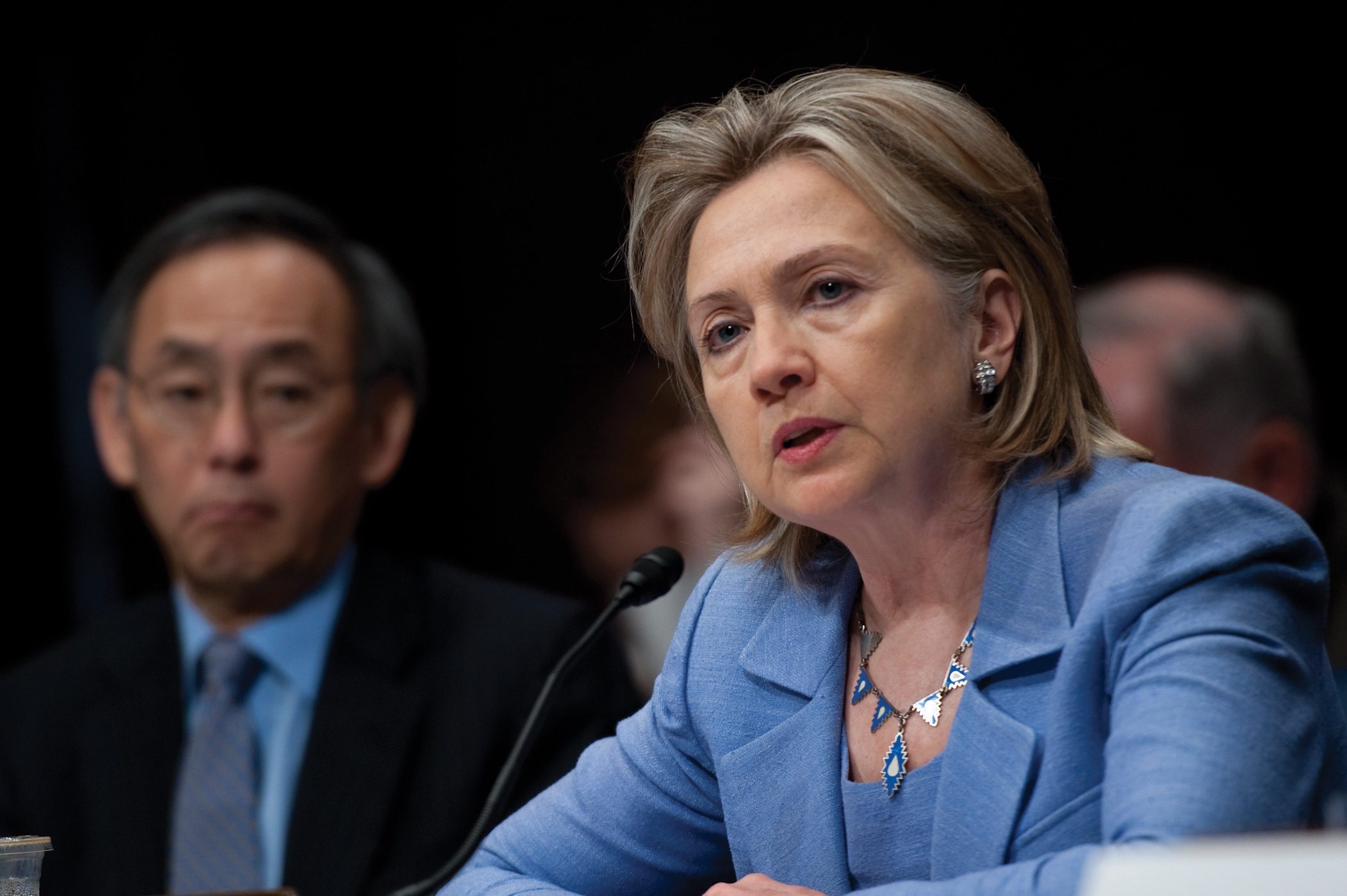

Figure half dozen.11

Secretary of Country Hillary Clinton is one of an increasing number of women who has accomplished a highly visible political leadership role.

There are significant differences in the style that males and females are socialized to politics. Historically, men have occupied a more fundamental position in American political civilisation than women. This tradition was institutionalized at the time of the founding, when women did not receive the right to vote in the Constitution. While strides take been made over the past century to achieve political equality between the sexes, differences in sex-role socialization still exist. Traits associated with political leadership, such as being powerful and showing authority, are more often associated with males than females. Girls have fewer opportunities to observe women taking political action, particularly as few females hold the highly visible positions, such as member of Congress and chiffonier secretary, that are covered past mass media. This is starting to change equally women such as Madeleine Albright and now Hillary Clinton attract media attention in their roles equally secretarial assistant of state or as Nancy Pelosi did as Speaker of the House of Representatives. Sarah Palin gained national attention equally Republican John McCain's vice presidential running mate in 2008, and she has become a visible and outspoken political figure in her ain right. Despite these developments, women are still are socialized to supporting political roles, such equally volunteering in political campaigns, rather than leading roles, such equally holding higher-level elected office. The result is that fewer women than men seek careers in public part beyond the local level (Sapiro, 2002).

Political Generations

A political generation is a grouping of individuals, similar in age, who share a full general set of political socialization experiences leading to the development of shared political orientations that distinguish them from other age groups in gild. People of a similar historic period tend to be exposed to shared historical, social, and political stimuli. A shared generational outlook develops when an historic period group experiences a decisive political upshot in its impressionable years—the menstruum from tardily boyhood to early machismo when people arroyo or accomplish voting historic period—and begins to think more seriously about politics. At the same time, younger people have less clearly defined political beliefs, which makes them more than probable to be influenced by central societal events (Carpini, 1986).

The idea of American political generations dates back to the founding fathers. Thomas Jefferson believed that new generations would emerge in response to irresolute social and political conditions and that this would, in turn, influence public policy. Today people can be described equally being role of the Depression Era/GI generation, the silent generation, the baby smash generation, generation X, and the millennial generation/generation Y. Depression Era/GIs, born between 1900 and 1924, were heavily influenced by Earth War I and the Great Depression. They tend to trust government to solve programs because they perceived that Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal programs helped the land recover from the Depression. The silent generation, born between 1922 and 1945, experienced World War Two and the 1950s during their impressionable years. Like their predecessors, they believe that regime tin can get things washed, just they are less trusting of leaders. The Vietnam War and the civil rights and women'due south rights movements left lasting impressions on the baby boomers, who were built-in between 1943 and 1960. The largest of the generations, this cohort protested confronting the government establishment in its youth and nonetheless distrusts government. Generation Xers, born between 1965 and 1980, came of historic period during a menstruation without a major war or economic hardship. The seminal events they relate to are the explosion of the Challenger spacecraft and the Iran-Contra hearings. This generation developed a reputation for defective both knowledge and interest in politics (Strauss & Howe, 1992). The political development of the millennials, those born between 1981 and 2000, is influenced by the terrorist attacks of 9/xi and its aftermath, as well as past the rise of digital technologies. This generation is more multicultural and has more than tolerance for racial and indigenous divergence than older cohorts. Sociologists William Strauss and Neil Howe have identified an emerging cohort born after 2000, which they label the homeland generation. This generation is influenced past omnipresent applied science, the war on terror, and parents who seek to protect them from societal ills (Strauss & Howe, 2000).

Conflicts betwixt generations accept existed for centuries. Thomas Jefferson observed meaning differences in the political worldviews of younger and older people in the early on days of the republic. Younger government leaders were more willing to adjust to changing conditions and to experiment with new ideas than older officials (Elazar, 1976). Today generation Xers and the millennials have been portrayed as self-interested and lacking social responsibility past their elders from the baby smash generation. Generational conflicts of different periods have been depicted in landmark films including the 1950s-era Insubordinate without a Cause and the 1960s-era Piece of cake Rider. Generation Ten has been portrayed in films such as Slacker, The Breakfast Society, and Reality Bites. Movies nigh the millennial generation include Easy A and The Social Network.

Fundamental Takeaways

Political socialization is the procedure past which people learn about their authorities and acquire the behavior, attitudes, values, and behaviors associated with skilful citizenship. The political socialization process in the United States stresses the instruction of democratic and backer values. Agents, including parents, teachers, friends, coworkers, church building assembly, club members, sports teams, mass media, and pop culture, pass on political orientations.

Political socialization differs over the life grade. Young children develop a basic sense of identification with a state. Higher students can form opinions based on their experiences working for a cause. Older people can get agile because they see a need to influence public policy that volition affect their lives. At that place are subgroup differences in political socialization. Sure groups, such citizens with college levels of education and income, are socialized to take an active part in politics, while others are marginalized.

Political generations consist of individuals similar in age who develop a unique worldview every bit a result of living through item political experiences. These cardinal events include war and economical depression.

Exercises

- Practice you believe you have the ability to brand an impact on the political process?

- What is the starting time political result you were aware of? What did you recollect almost what was going on? Who influenced how you idea about it?

- How practice members of your political generation feel well-nigh the government? How do your attitudes differ from those of your parents?

References

Almond, G. A. and James S. Coleman, eds., The Politics of the Developing Areas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960), 27.

Alwin, D. F., Ronald L. Cohen, and Theodore Thou. Newcomb, Political Attitudes Over the Life Bridge (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991).

Carpini, M. X. D., Stability and Change in American Politics (New York: New York University Press, 1986).

Conover, P. J., "Political Socialization: Where'southward the Politics?" in Political Science: Looking to the Future, Volume Three, Political Behavior, ed. William Crotty (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1991), 125–152.

Craig, Due south. C., Malevolent Leaders (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993).

Dawson, R. E. and Kenneth Prewitt, Political Socialization (Boston: Little Brown and Visitor, 1969).

Dennis, J., David Easton, and Sylvia Easton, Children in the Political Organization (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969).

Dennis, J. and Diana Owen, "The Partisanship Puzzle: Identification and Attitudes of Generation X," in After the Smash, ed. Stephen C. Craig and Stephen Earl Bennet (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997), 43–62.

Dey, East. Fifty., "Undergraduate Political Attitudes," Journal of College Didactics, 68 (1997): 398–413.

Elazar, D. J., The Generational Rhythm of American Politics (Philadelphia: Temple Academy, Eye for the Study of Federalism, 1976).

Greenstein, F. I., Children and Politics (New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press, 1969).

Hahn, C. 50., Becoming Political (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998).

Harris, J. R., "Where Is the Kid'south Environs? A Group Socialization Theory of Evolution," Psychological Review 102, no. iii (1995): 458–89.

Hess, R. and Judith Torney, The Development of Political Attitudes in Children (Chicago: Aldine, 1967).

Hyman, H., Political Socialization (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1959), 69.

Kaiser Family unit Foundation, The Media Family unit (Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006).

Langton, G. P., Political Socialization (New York: Oxford, 1969).

Lindblom, C. E., "Another Sate of Listen," in Subject and History, ed. James Farr and Raymond Seidelman (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1993), 327–43.

Lyons, P., Class of '66 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994).

McDevitt, M. and Steven Chaffee, "From Top-Down to Trickle-Up Influence: Revisiting the Assumptions about the Family in Political Socialization," Political Communication, November 2002, 281–301.

Merelman, R. M., "The Family and Political Socialization: Toward a Theory of Exchange," Periodical of Politics, 42:461–86.

Merelman, R. M., Making Something of Ourselves (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

Merriam, C. E., The Making of Citizens (Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1931), 160–61.

Miles, A. D., "A Multidimensional Approach to Distinguishing between the Most and To the lowest degree Politically Engaged Senior Citizens, Using Socialization and Participation Variables" (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 1997).

Nie, N. H., Jane Junn, and Kenneth Stehlik-Barry, Educational activity and Autonomous Citizenship in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Niemi, R. G. and Jane Junn, Civic Education (New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Printing, 1998).

Niemi, R. G. and Mary A. Hepburn, "The Rebirth of Political Socialization," Perspectives on Political Scientific discipline, 24 (1995): vii–16.

Padilla, F., The Gang equally American Enterprise (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992).

Riccards, M. P., The Making of American Citizenry (New York: Chandler Press, 1973).

Saphir, Chiliad. North. and Steven H. Chaffee, "Adolescents' Contribution to Family Communication Patterns," Human Communication Research 28, no. one (2002): 86–108.

Sapiro, V., The Political Integration of Women (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983).

Sapiro, V., Women in American Society (New York: Mayfair Publishing, 2002).

Steckenrider, J. Due south. and Neal Eastward. Cutler, "Aging and Adult Political Socialization," in Political Learning in Adulthood, ed. Roberta S. Sigel (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 56–88.

Strauss, West. and Neil Howe, Millennials Ascension (New York: Random House, 2000).

Strauss, W. and Neil Howe, Generations (New York: William Morrow, 1992).

Walker, L. J., Karl H. Hennig, and Tobias Krettenauer, "Parent and Peer Contexts for Children's Moral Reasoning Evolution," Child Development 71, no. 4 (August 2000): 1033–48.

ferrellovelinterst.blogspot.com

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/americangovernment/chapter/6-2-political-socialization/

0 Response to "What Role Does the Family Play on Political Socialization"

Post a Comment